Our research group is applying “systems” and supramolecular ways of thinking to solve problems in catalysis and the chemical origins of life.

1) Self-organized reaction networks to understand the origin of life

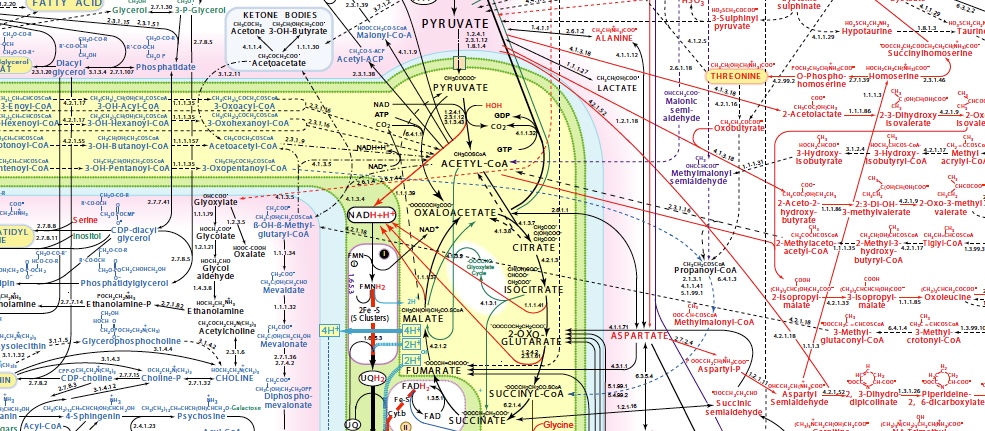

How did the self-organized chemistry that gave rise to life emerge before there were enzymes to act as catalysts? Why does biochemistry use the reactions and pathways that it does and not others? How did chemical reactions networks become more complex and life-like before genes? What sorts of environments can enable all this? This twice ERC-funded project aims to understand the prebiotic origins of biological metabolism.

Recreating an origin of life in the lab is essential for a deep understanding of biology. In several areas of science, systems are found to organize themselves in a dynamic way when an energetic stress is applied under specific constraints; the emergence of life in the form of self-organized chemistry should also have satisfied this criteria. Our lab has implemented a search strategy to identify conditions under which geochemistry might organize itself into dynamic chemical reaction networks that embody features of metabolism and its bioenergetics.

In the first phase of our search, we found experimental conditions that enable many of the individual reactions in the core of anabolism without enzymes, strengthening the case that the core anabolic network might have initiated nonenzymatically. We have found or studied nonenzymatic chemistry that resembles the acetyl CoA pathway [1,2], parts of the reverse Krebs cycle [3,4], the Krebs cycle and the glyoxylate cycle [5], reductive amination and transamination to form amino acids from ketoacids [6,7], and pyrimidine nucleobase biosynthesis[8]. The need for metals such as Fe, Ni, or Co was a recurring result of these studies.

In a second phase, we experimentally found that products of the metabolic network, today known as coenzymes, could act to nonenzymatically promote the reactions that produced them or to enable new reactions that were not possible until their emergence. We found that PLP [9], NADH[10], and ADP [11] can all nonenzymatically promote or catalyze reactions (transamination, keto acid reduction, and phosphorylation of NDPs to NTPs, respectively) required for their own biosynthesis. This reactivity depends on the same two metals (Fe3+ or Al3+) in all cases, implicating at least one of them in the origin of metabolism. These experiments support a model in which a primitive nonenzymatic metabolic network could have been pruned and expanded through catalytic feedback effects, leading to self-complexification and increased catalytic autonomy from the environment even before genes or enzymes.

In the third ongoing phase of our work, we integrate knowledge from the first two phases to propose and test environments that might allow self-organized reaction networks to emerge.

For a now slightly out of date review, see [13]. See also below for recent recorded talks.

[1] Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1019. [2] Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 534. [3] Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1716. [4] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202212932. [5] Nature 2019, 569, 104. [6] J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 19099. [7] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202212237. [8] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202117211. [9] J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13357. [10] Chem 2024, accepted. [11] J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21630 [12] Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7708.

May 5, 2021

November 8, 2022

2) Catalytic Synthetic Methodology

We are broadly interested in the development of new catalytic methods for organic synthesis. Recent interests include specific solvent effects (particularly nitromethane and HFIP) on the direct nucleophilic substitution of alcohols [1], alkyl fluorides [2]; the ring opening of cyclopropanes [3] and epoxides [1c, 4]; alkene hydrofunctionalization [5,6]; the difunctionalization of alkenes [7] . We are also interested in extending the scope of cross-coupling reactions to include a broader range of functional groups [8].

[1] (a) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3085. (b) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9555. (c) Chem 2021, 7, 3425. [2] ACS Catalysis 2016, 6, 3670. [3] (a) Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 574. (b) Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6411. [4] ACS Catalysis 2022, 12, 3309. [5] ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10995. [6] Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8436. [7] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, online. [8] (a) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 14959. (b) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25307.

For more information on ongoing projects, please contact Dr. Moran directly.

3) Vibrational Strong Coupling applied to organic chemistry and catalysis

This project aims to develop a completely new way to control the rate and selectivity of organic reactions: by selectively modifying relevant molecular vibrations by running the reaction between appropriately-spaced mirrors. Vibrational Strong Coupling (VSC) is an emerging field in the quantum optics community. A collaboration between our group (organic chemistry) and the group of Prof. Thomas Ebbesen (a world leader in VSC), aims to exploit this phenomenon for use in organic synthesis and catalysis. Thus far, we have shown that VSC can be used to change the rates [1], chemoselectivity [2] and stereoselectivity [3] of ground state organic reactions. Ongoing work aims to understand and predict how VSC influences chemistry, to develop it as a tool for mechanistic insight, and to exploit it to streamline the outcomes of useful chemical transformations.

[1] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11462. [2] Science 2019, 363, 615. [3] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5712.

Previous projects:

4) Catalyst discovery using complex mixtures – a systems approach

We have developed a simple algorithmic approach for screening and deconvoluting complex mixtures of catalyst components with the goal of rapidly identifying new catalysts and cooperative effects. We have used this strategy to uncover new organoboron [2] and nickel [2,3] catalysts, and have found that catalysts selected in this way tend to be useful in multicatalysis.[4] Our method has recently been implemented by Boehringer-Ingelhgeim in the evaluation of all Cu-catalyzed C-N couplings, one of the most widely used reactions in the pharmaceutical industry.[5]

[1] For an account of our recent work in this area, see: Synlett 2016, 27, 2637. [2] Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2501. [3] J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 6922. [4] Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 12274. [5] J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 1528.